Last week, this post discussed the use of sentence-diagramming to help determine the correct case for certain relative pronouns. This week, Ms. Picky would like to continue that theme to illustrate how to determine the case of other relative and personal pronouns—but she would also like to point out to the gallery (before the gallery points it out to her) that, unless one is at a grammarians’ convention, there is at least one occasion when being grammatically correct is being . . . a pompous ass.

What is under discussion today is choosing between I and me, she and her, he and him, they and them, or who and whom—i.e., whether a particular pronoun should be in the objective case or the subjective (nominative) case.

We need to begin with discussing a particular type of verb: a linking, or copulative, verb, because that is the kind of verb that links its subject and its predicate nominative. Ms. Picky will explain.

The first and most obvious example of a linking verb is any form of the verb “to be,” such as:

is,

am,

are.

But there are others as well, such as:

seems,

becomes,

appears.

Let’s take the sentence “She is my sister.” In this sentence, the word “sister,” which follows the linking verb “is,” is understood to be the equivalent of the subject, “she.” When such equivalency occurs—when the person or thing that follows the verb is understood to be the same person or thing as the subject—you have an example of a predicate nominative:

He is the one for me.

(“He” and “one” are the same, or equivalent.)

Those two paintings are the best examples of his art.

(“Paintings” and “examples” are the same, or equivalent.)

We are the lucky ones.

(“We” and “ones” are the same, or equivalent.)

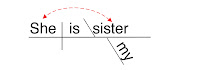

“One,” “examples,” and “ones” are all predicate nominatives. The diagram of “She is my sister,” below, shows the relationship between the predicate nominative and the subject. The oblique line following “is” indicates that what follows “is” refers back to—and is the same as—what precedes it: It “points” you in the direction of the subject:

All right, let’s bump it up a notch by looking at a more complex sentence:

She is the one [who/whom] I like.

The diagram illustrates the words’ relationships in the sentence, which determine whether one would use “who” or “whom.”

Here’s the script of the main clause [She is the one]:

Q. What is the verb (or “simple predicate”)?

A. Is.

To determine the subject:

Q. Who or what is?

Q. Who or what is?

A. She is.

To determine the predicate nominative:

Q. She is what?

Q. She is what?

A. She is the one.

And here’s the script of the relative clause [whom I like]:

Q. What is the simple predicate?

A. Like.

To determine the subject:

Q. Who or what likes?

Q. Who or what likes?

A. I like.

To determine the object:

Q. I like what?

Q. I like what?

A. I like whom.

In the dependent clause, we can now see that the relative pronoun (who or whom) is the object of the simple predicate, or verb, (like) and, since it is the object, it must be in the objective case: whom.

All right, now [you are saying], what was it you mentioned in the beginning: What is the occasion when, if one is being grammatically correct, one is being a “pompous ass”?

Here it is:

Knock, knock.

Q. Who’s there?

A. It’s [I or me].

Whoever answers “It’s I” is being perfectly correct. But he is also being a pompous ass.

_________

Bulletin Board

To J.W.: In the U.S., one does not use single quotation marks for references to titles, words as words, nicknames, or for any other purpose except for quotes within quotes. Other nations have different styles.

(

Ms. Picky is currently engaged in trying to persuade immigration officials at the various English-speaking nations’ points of entry to pass out brochures indicating their national rules for spelling and punctuation.)

Examples:

In the poem “The Road Not Taken,” what is the symbolism of “the road”?

Sean “the Mayor” Casey was at first base.

“I hope you were joking,” she said, “when you referred to that clown as ‘the next president of the United States.’ ”

No comments:

Post a Comment